Common Law Trademark Basics:

Priority of Use and Distinctiveness are Key

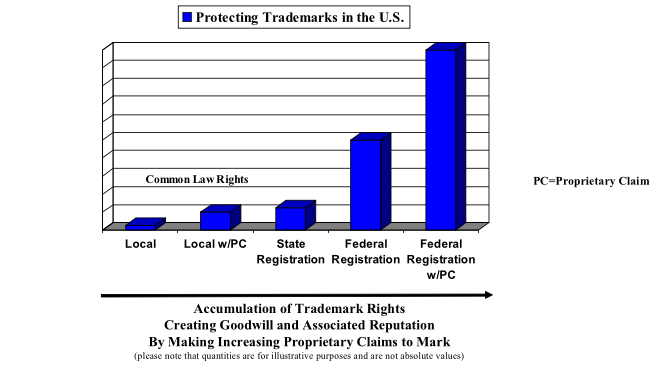

Common Law Rights Are Two Giant Steps Below Federal Principal Registration Rights

United States trademark rights are acquired by, and dependent upon, priority of use and distinctiveness. Distinctiveness arises from the uniqueness of the choices of the word(s), term, name, symbol, or device, or any combination of these that are used to identify goods or services that a trademark owner has an exclusive right to claim for their own. Registration on the Principal Register goes beyond the rights earned under common law.

Federal Registration Expands the Reach of a Trademark

[T]he scope of federal trademark protection differs significantly from the scope of common law protection: Congress expanded the common law ... by granting an exclusive right in commerce to federal registrants in areas where there has been no offsetting use of the mark.... Congress intended the Lanham Act to afford nation-

Natural Footwear Ltd. v. Hart, Schaffner & Marx, 760 F.2d 1383 (C.A.3 (N.J.), 1985).

Priority or First to Use

The ‘First to Use’ a trademark (the use that has priority) acquires rights in that mark if the mark is inherently strong and if the trademark follows other common law principals. Inherent strength is not something that is automatically present in common words, phrases or designs. If your trademark is made up of the KEY WORDS that describe your product, components, customers, uses or other words or phrases that you would type into a search engine box, your trademark may not be a trademark at all but just a collection of words or perhaps a trade name. A trademark that is made up entirely of descriptive words may not acquire any common law rights because one user cannot take those words out of circulation for other people to use to describe the same products or services and cannot claim them for exclusive use.

Potential trademarks and parts of potential trademarks that are not inherently distinctive, such as those that only contain words or designs that describe the product or service being sold or those who would use the product or service (also called merely descriptive trademarks), are not given strong legal rights when first used but may acquire legal rights over time or with lots of advertising or use. If the potential trademark or part of the potential trademark is generic, meaning that it identifies the class of products or services, the generic terms have no trademark rights and cannot acquire legal rights over time.

The date when a business obtains common law rights in a trademark (sometimes know as “trade identity rights’) depends on the distinctiveness of the mark. “A business will obtain rights in the mark upon first use only if the mark is inherently distinctive. If the mark is not inherently distinctive, a business may obtain ownership rights in the mark when the mark attains a secondary meaning.” Coach House Restaurant, Inc. v. Coach and Six Restaurants, Inc., 934 F.2d at 1559 (C.A.11 (Ga.), 1991). Even if someone uses something as a trademark, “if it is not distinctive, the user does not have a trademark because he has no existing trademark rights.” Otto Roth & Company, Inc. v. Universal Foods Corporation, 640 F.2d 1317 (Fed. Cir. 1981).

Potential trademarks that are not distinctive or would not be awarded rights for other reasons such as primarily being a surname* (may be refused registration as a surname refusal) may also acquire distinctiveness. Potential trademarks that start out weak because they are descriptive may acquire additional trademark rights called secondary meaning or acquired distinction after a period of time if a number of other factors are present.

* Two surname issues can exist from the same use:

1) TMEP 1206.02 [Surnames in ] Connection With Goods or Services: Whether consent to registration [of a surname] is required depends on whether the public would recognize and understand the mark as identifying a particular living individual. A consent is required only if the individual will be associated with the goods or services, either because: (1) the person is generally known or so well known in the field relating to the goods or services that the public would reasonably assume a connection; or (2) the individual is publicly connected with the business in which the mark is used. Krause v. Krause Publications, Inc., 76 USPQ2d 1904 (TTAB 2005), aff’d per curiam, No. 2007-

TMEP 1211 Refusal on Basis of Surname: [Extracted from 15 U.S.C. §1052] No trademark by which the goods of the applicant may be distinguished from the goods of others shall be refused registration on the principal register on account of its nature unless it ... (e) Consists of a mark which ... (4) is primarily merely a surname.

Where Do Common Law Trademark Rights Apply?

Common law trademark rights (where defined by state law, local law, case law or federal unfair competition laws) exist where trade has taken place that qualifies as trademark use (or trade name use or service mark use) which traditionally used to be in the isolated local geographic areas where the trade actually took place or where the MARK was actually used. When someone from one state can order from someone in another state on a worldwide web and that product is shipped on a interstate freeway to another state or the service is provided in another state, the idea of local trade is questionable. One state’s law has these definitions:

MARK. Any trade name, trademark, or service mark entitled to registration under this article whether registered or not.

USED. A mark shall be deemed to be used in this state:

a. On goods or their containers or the displays associated therewith or on the tags or labels affixed thereto when such goods are sold or otherwise distributed in the state;

b. In connection with services when it is used or displayed in the sale or advertising of services and the services are rendered in this state; and

c. In connection with a business when it identifies the business to persons in this state.

Does local even exist anymore? Use of internet web sites for selling throughout the U.S. may change the scope of where common law rights exist and how they can be protected and enforced. Sometimes this means you can get a cease and desist letter at your small business in a small town on the East Coast from a big city West Coast business for using a confusingly similar trademark on the internet to promote a local business. Success can bring its own problems.

It’s all about goodwill, the more successful that a trademark is for helping consumers to make a positive connection between a product or service and who provides it, the more likely it is that someone will try to compete by taking the trademark or something similar (may be OK) or confusingly similar (may be infringement) to use it for themselves. Some businesses may do it intentionally: Why take the time to build goodwill when you can use a name that is already associated with goodwill? Some businesses may do it unintentionally: Why should I verify that I have a right to use a name when I like the name and it costs money to verify that it is not being used already and I Googled it and nothing came up?

Common law rights can be used to stop someone else’s use. A common law mark may be able to successfully oppose a confusingly similar federal registration or cancel a federally registered trademark if the trademark compete in the same or similar products or services in the same geographical area if the alleged common law trademark owner can show prior use (or senior use) of the mark. The Lanham Act provides that a registered mark, even if it has become incontestable, still may be challenged "to the extent, if any, to which the use of a mark registered on the principal register infringes a valid right acquired under the law of any State or Territory by use of a mark or trade name continuing from a date prior to the date of registration under this chapter of such registered mark." 15 U.S.C. 1065 as quoted in Advance Stores Co. Inc. v. Refinishing Spec. Inc., 188 F.3d at 411 (6th Cir., 1999). A challenge to a registered mark by an unregistered mark could be in a USPTO opposition or cancellation or in a state or federal court.

Why not just stick with common law rights? Enforcement can be difficult from both sides. Trying to enforce a common law right may mean one do over after another. Stopping one person from using your name may cost more than a federal registration would have cost in the first place and when you are done stopping the first person you still just have a common law right that you are going to have to keep enforcing on a piecemeal basis. If this first use by someone else is a federal registration of the mark by a junior user, the junior user will have a much easier time stopping you than you will have in stopping them. (Federal registrations have presumptive rights.) Many third parties such as Facebook, Twitter, domain name registrars, web site hosts, and others have policies that protect federal registrations. Someone else who registers your common law name will have presumptive rights in that mark and trying to stop them can be very difficult and expensive and the cause of a lot of heart ache and distress.

Common law trademarks do not enjoy the advantages of federal registration (see below) which include being protected more thoroughly from infringement and counterfeiting trademarks. Can’t get federal registration? Marks that do not qualify for federal registration may not qualify for common law protection for the same reasons: federal laws are based on the same or similar common law principles. Likewise, having a federal registration does not protect a business from being challenged by a senior user of a common law trademark. USPTO trademark examiners do not examine potential trademarks for potential infringement by state or common law marks. The USPTO only looks at other USPTO federal registrations for potentially conflicting marks.

Unregistered Trademarks

Unregistered trademarks are protected by law under more than just common law (case law) because various state statutes and federal statutes have adopted (codified) the concepts and terminology that were developed in case law. One applicable federal law for unregistered trademarks is 15 USC § 1125(a) of the Lanham Act: False designations of origin, false descriptions, and dilution forbidden (a) Civil action:

(1) Any person who, on or in connection with any goods or services, or any container for goods, uses in commerce any word, term, name, symbol, or device, or any combination thereof, or any false designation of origin, false or misleading description of fact, or false or misleading representation of fact, which—

(A) is likely to cause confusion, or to cause mistake, or to deceive as to the affiliation, connection, or association of such person with another person, or as to the origin, sponsorship, or approval of his or her goods, services, or commercial activities by another person, or

(B) in commercial advertising or promotion, misrepresents the nature, characteristics, qualities, or geographic origin of his or her or another person’s goods, services, or commercial activities;

shall be liable in a civil action by any person who believes that he or she is or is likely to be damaged by such act.

Claims for trademark infringement for unregistered marks require findings that the unregistered marks owned by plaintiff are either inherently distinctive [rather than descriptive] or have acquired a secondary meaning and are likely to be confused with defendants' marks by members of the relevant public. Duncan Mcintosh Co. v. Newport Dunes Marina LLC, 324 F.Supp.2d 1083-

In addition, an unregistered mark must actually have been used as a trademark to be protected under trademark law. "[A] plaintiff must show that it has actually used the designation at issue as a trademark"; thus the designation or phrase must be used to "perform[] the trademark function of identifying the source of the merchandise to the customers." Microstrategy Incorp. v. Motorola, 245 F.3d at 341 (4th Cir., 2001) quoting Rock & Roll Hall of Fame v. Gentile Prods., 134 F.3d 749, 753 (6th Cir. 1998). See valid manner examples below or the web site Function As a Mark.com for examples on how a trademark should function.

Geographic Rights for Unregistered Marks are Limited

A common law mark (unregistered mark) has geographically limited rights (prior use) against a subsequent user under the Tea Rose/Rectanus doctrine -

This prior use right may be enforced through an opposition or cancellation proceeding. See Published for Opposition see also Opposition Steps/Cancellation Steps for more information.

Secondary Meaning

Secondary meaning is when the consuming public has made a link between an alleged mark and the source of the mark. The assumption with secondary meaning or acquired distinctiveness is that there was some original reason that the mark did not qualify for protection such as not being inherently distinctive.

The factors considered in determining whether a descriptive mark (not inherently distinctive) has achieved secondary meaning include:

(1) whether actual purchasers of the product bearing the claimed trademark associate the trademark with the producer as evidenced by survey or direct consumer testimony;

(2) the degree and manner of advertising under the claimed trademark;

(3) the length and manner of use of the claimed trademark; and

(4) whether use of the claimed trademark has been exclusive.

Levi Strauss & Co. v. Blue Bell, Inc., 778 F.2d 1352, 1358 (9th Cir.1985).

Has your common law mark acquired distinctiveness or secondary meaning? Tired of just Supplemental Registration? Not Just Patents® Legal Services can analyze the facts of your situation to prepare an affidavit of acquired distinctiveness , if applicable, for your use in a trademark application is your mark lacks inherent distinctiveness and has been refused or if you are starting out with a new application.

State Registration

State Registration of a non-

Obtaining a state registration does not, however, allow an alleged trademark owner to mislead the public into believing that your business is that of another business by using the same or a confusingly similar mark. Obtaining a state registration does make a mark easier to find than no registration at all which may act as somewhat of a deterrent to another business from adopting your trademark without your consent. As with federal registration, it is up to the state trademark owner to enforce their own rights by monitoring use of conflicting marks and pursuing infringers, the state merely provides a forum to sue infringers. Some states have enhanced counterfeiting laws to protect tourism and other local business and provide criminal penalties against counterfeiting. See Federal and State IPR Laws for a chart of many federal and state laws regarding Intellectual Property Rights (IPR).

Most states that have passed trademark registration laws have preserved common law rights. The Lanham Act provides that a registered mark, even if it has become incontestable, still may be challenged "to the extent, if any, to which the use of a mark registered on the principal register infringes a valid right acquired under the law of any State or Territory by use of a mark or trade name continuing from a date prior to the date of registration under this chapter of such registered mark." 15 U.S.C. 1065 as quoted in Advance Stores Co. Inc. v. Refinishing Spec. Inc., 188 F.3d at 411 (6th Cir., 1999). See Federal and State IPR Laws for more information. See http://strongtrademark.com/incontestability.html for more information on incontestability.

Verify/Check Whether Your Claimed Trademark Is Trademarkable

1. Verify/Check Inherent Strength Does each trademark consist of inherently distinctive element(s) that can be claimed for exclusive use?

Marks that are merely descriptive (or worse, generic) are hard to register and hard to protect. Section 2(e) refusals are very common refusals. Whether a trademark is merely descriptive depends on the goods and services description.

2. Verify/Check Right to Use Does the trademark have a likelihood of confusion with prior-

Section 2(d) refusals are very common refusals.

3. Verify/check Right to Register Does the trademark meet the USPTO rules of registration? (Does not have any grounds for refusal?)

4. Verify/check Specimen Is the trademark used as a trademark or service mark in the specimen?

Specimen refusals are very common refusals. The right type of specimen for any particular application depends on what the goods or services are.

5. Verify/check Goods and Services ID Is the goods/services identification definite and accurate? Is the goods/service ID as broad as it should be under the circumstances or will a narrower description distinguish it better?

ID refusals are common too but getting the right description identifies the scope of protection. Too narrow of a description can yield narrow rights. Too broad of a description can result in an unnecessary likelihood of confusion with someone else.

Go Beyond Just Trademarkable To A Strong Mark: Aim Higher

Do you know the answers to these questions?

- Can I claim exclusive rights to use this trademark?

- Does this trademark meet the qualifications for being registered on the USPTO Principal Register? Is it trademarkable?

- Is this trademark strong enough that others would want to license it from me?

- Does this trademark have potential to extend to other product lines?

- Is this mark inherently distinctive?

- Are there others users of this mark that could prevent me from using this mark or would sue me or prevent me from getting federal registration because they can prove they are prior users?

- Are there valid reasons for someone to oppose or cancel the mark because the mark doesn’t qualify for protection or because they have superior rights?

- Would the USPTO find a likelihood of confusion with someone else’s registered or pending trademark and prevent my registration of this mark?

- Would a court enforce the use of this trademark?

- Do I have to somehow acquire distinctiveness for this mark before it would be recognized as being trademarkable?

- Does this mark use such common terms that it would be called a weak trademark?

- Is this mark descriptive or deceptive or geographically descriptive?

- Do I use the mark in a way that increases my rights or am I using it in a way where it does not function as a trademark?

These are all good questions to consider before adopting a trademark for use because if you are planning to succeed, it may be a good idea to be able to work that plan rather than abandoning it. [The abandonment rate of trademark applications at the USPTO (trademarks that did not issue) is very high, about half of applications never register.]

All of the above questions involve fact-

Not Just Patents ® and Aim Higher® are federally registered trademarks of Not Just Patents LLC for Legal Services.

|

Trademark Rights |

Principal Register |

Supplemental Register |

Common Law |

|

Bring infringement suit in federal court based on the federal registration |

YES |

YES |

NO |

|

The owner of a USPTO registration is entitled to rely upon the USPTO's fulfillment of its statutory duty to refuse registration to marks confusingly similar to a prior registrant's mark (USA Warriors Ice Hockey Program, Inc., 122 U.S.P.Q.2d 1790, (TTAB 2017)) |

YES |

YES |

NO |

|

Mark is easy to find for search reports |

YES |

YES |

NO |

|

Owner can use ® to symbolize federal registration |

YES |

YES |

NO |

|

Incontestability of mark after 5 years |

YES |

NO |

NO |

|

Statutory presumption of validity |

YES |

NO |

NO |

|

Statutory presumption of ownership |

YES |

NO |

NO |

|

Statutory presumption of distinctiveness or inherently distinctive |

YES |

NO |

NO |

|

Statutory presumption of exclusive right to use the mark in commerce |

YES |

NO |

NO |

|

Can be recorded with US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to prevent importation of infringing goods |

YES |

NO |

NO |

|

Ability to bring federal criminal charges against traffickers in counterfeits |

YES |

NO |

NO |

|

Use of the U.S. registration as a basis to obtain registration in foreign countries |

YES |

NO |

NO |

TMk App.com

TESS & TEAS Application Hacks

TMk®

Not Just Patents®

Aim Higher® Facts Matter

W@TMK.law best or

1-

(Calls are screened for ‘trademark’ and other applicable reasons for the call)

|

TMk® Email W@TMK.law best or call 1- For more information from Not Just Patents, see our other pages and sites: |

|

|

Are You a Content Provider- |

|

|

Trademark Register FAQ Definition: Clearance Search teas plus vs teas standard approved for pub - |

Amend to Supplemental Register? |

|

|

|

|

ID of Goods and Services see also Headings (list) of International Trademark Classes How to search ID Manual |

How to TESS trademark search- |

|

Likelihood of confusion- |

|

|

Published for Opposition What is Discoverable in a TTAB Proceeding Affirmative Defenses |

|

|

What is the Difference between Principal & Supplemental Register? |

What is a Family of Marks? What If Someone Files An Opposition Against My Trademark? Statutory Cause of Action (aka Standing) |

|

©2008- Email: W@TMK.law. This site is for informational purposes only and is provided without warranties, express or implied, regarding the information's accuracy, timeliness, or completeness and does not constitute legal advice. No attorney/client relationship exists without a written contract between Not Just Patents LLC and its client. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Privacy Policy Contact Us

|

|